That’s me, standing in front of about seventy third graders in Guilford, CT at the Calvin Leete Elementary School on Friday the 13th of April. In the air are the wiggly hands of nearly seventy third grade students. Why?

Because I asked them: “How many of you have a stone wall in your backyard or in a nearby place?” The hands shot up. The enthusiasm was palpable. Every student, it seemed, wanted to tell me about their own favorite wall.

The four classroom teachers and their staff were quite proud of their student’s excitement about the subject, which had just been introduced as part of their earth-science curriculum. They will be linking this subject to other subjects required by the curriculum, namely language arts, science, history, art, and mathematics. I was there to read and discuss the award-winning illustrated children’s book, Stone Wall Secrets, for which we wrote a curriculum several years ago.

During my many years of visiting classrooms, I’ve found that elementary school kids like these are no less interested in stone walls than in dinosaurs, volcanoes, and glaciers. All it takes is a teacher willing to embrace stone walls –New England’s signature landform– as a launching pad for their earth science teaching, rather than the more national generic menu offered by the national publishers. Did you know that dinosaur footprints, lava flows, and glacier-marks have all been found on the stones within the region’s walls? Indeed, these three phenomena are but chapters in the grander story of New England’s stone walls.

Two days later, I was standing in front of an altogether different group. All were over thirty and most were senior citizens. This was the Middletown (RI) Historical Society, located in a town that occupies the bulk of Aquidneck Island in Narragansett Bay, and is responsible for its best beaches. To the south and north are the more well known towns of Newport and Portsmouth, respectively.

This rural residential town is one of three in the state having an ordinance for the protection of stone walls. Congratulations for their foresight. This much-older group was equal to the third-grade children of Guildford in terms of their enthusiasm, and they were the ones asking the questions. In fact, there were so many questions early on that my talk went overtime, forcing the reporter and photographer sent by the Newport Daily News to leave early.

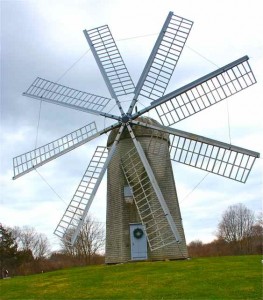

The most iconic item in the historical society’s collection is a spectacular windmill reconstructed in Paradise Park, adjacent to the society’s small museum, a one-room schoolhouse on the National Register of Historic Places. When rigged with all eight sails, Boyd’s windmill, built in 1810, provided the power to rotate one grinding stone above another to convert historic Rhode Island’s grain into flour.

Its pair of cylindrical grinding stones –one intact, and one broken– provide a perfect example of what I call a “Notable Stone” in my taxonomy. Though both were made of durable granite, the top one broke with what engineers call “stress fatigue,” the accumulated result of too many vibrations for too many years.

Though the grinding stones were fascinating, I thought that the local stone walls were even cooler than the millstones. Though built recently, they capture not only the local style of the well-built historic walls, but also the relative abundance of the local stone in their proper proportions. The vast majority of rock on Aquidneck Island the gray to green-gray muddy sandstone and sandy mudstones known to geologists as the Narragansett Formation. The locals call it slate. In the photo below is a boulder of pudding stone (right) and a block of quartz from a vein. Both are common, but less abundant variations within the local rock.

These two recent SWI programs illustrate the range of interest in the phenomenon throughout New England. If you’re interested, contact me (Robert M. Thorson), the coordinator through this website.