I begin by sharing a variant of UConn’s statement of land acknowledgment. The “the land on which” the Stone Wall Initiative does its work “is the territory of the Eastern Pequot, Golden Hill Paugussett, Lenape, Mashantucket Pequot, Mohegan, Nipmuc and Schaghticoke Peoples who have stewarded this land throughout the generations.”

There is no question that indigenous stonework exists. It was well documented at several sites during the contact phase by early explorers, and some sites have been radiocarbon dated. However, the degree to which Indigenous stonework of “ceremonial stone landscapes” is significant in New England remains unsettled. For contrasting reviews consult.

Lucianne Lavin and Elaine Thomas, ed., Our Hidden Landscapes: Indigenous Stone Ceremonial Sites in Eastern North America (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2023).

Timothy H. Ives, Stones of Contention (Nashville, TN: New English Review Press, 2021).

My opinion is that each site must be investigated case by case. My general position was shared during my keynote talk for the 2010 Annual Meeting of NEARA, the New England Antiquities Research Association. A transcript is below, stripped of the slides

First, I’d like to thank the conference organizers, speakers, and attendees, especially to Glen Kreisberg for making the arrangements, and to Nick Bellantoni, who shared his thoughts with me during preparation of my talk.

Second, I really appreciate what you’re doing here. I speak of our shared interest in prehistory, in being outdoors, in companionship with one another. With academics, especially in the sciences, it’s often more competition than companionship.

I also really appreciate the fact that you volunteer some of your life energy in order to document and interpret the stone objects in our midst, whether in the deep woodlands, backyards, or in the case of a Fitchburg, Massachusetts, a perched boulder in the center of the town square. Like you, I’m interested in all things made of stone especially the odd stone wall among the mundane.

Your mission statement is the one I would write if I were an organization: “… a non-profit organization dedicated to a better understanding of our historic and prehistoric past through the study and preservation of New England’s stone sites in their cultural context. In 1964, when your group organized, I was an awkward, pimple-faced teenage boy only 13 years old.”

But above all, I appreciate your craving for mystery. I, too, experience genuine pleasure in knowing something while at the same time not knowing it completely. This keeps us on the edge of our intellectual seats, stimulating us to learn more, which keeps us young at heart.

In the fiction section of most public libraries the circulation of books from the mystery genre is so high that a separate section of shelves is usually required . From this observation, I can only conclude that normal people like us prefer mysteries to non-mysteries. Getting philosophical, perhaps this interest in mystery over non-mystery is a surrogate for the human pleasure of knowing that our lives are a mystery. To say that “life is a miracle,” is simply another way of saying life is a mystery.

Most of New England’s stone ruins clearly do not predate European exploration. Rather, they are part of an enormous constellation of stone structures created almost entirely by the agro-ecology of the Historic Period. Here, I refer to the obvious artifacts of that era such as stone walls, lanes, foundations, fills, and and freestanding piles. Here, I present a landquake model for the historic period stone structures about which you know much.

All culture groups use and rearrange materials within their human ecosystems, with northeastern Native Americans being no exception. The Algonquin and Iroquois precoursers to modern native nations made plenty of petroglyphs and inscribed stones. Why should they not also move stone around into structures?

One of those cultural groups were the Europeans. Their Neolithic tradition of stonework was present on Newfoundland by 1000 AD. Within the next six centuries, there are dozens of documented landings hither and yon along the northeastern shore, and probably hundreds of undocumented ones before initial settlement in 1607.

Hence, on theoretical grounds alone, I accept the virtual certainty than some of the stone features documented by NEARA are pre-historic….a word that I hesitate to use because it creates a false dichotomy.

The problem is one of scientific proof.

And now it’s time for a story. When I was a young geologist, I spent several years investigating and debunking claims for a pre-Clovis bone-tool culture from the Yukon Territory. There, archaeologists funded by what was then called the National Museum of Man, equivalent to the U.S. Smithsonian, they found thousands of broken pre-historic bones on the sandy and gravelly bars of winding rivers. From this vast collection, they culled a tiny residual fraction that had odd markings, mostly unusual breaks, scratches and flakes interpreted as artifacts. After several years of work including experimental replication, we demonstrated that this tiny fraction could have been created the effects of river ice, picking up bone and scratching, abrading, and percussion flaking it.

Hence, the main problem for NEARA is that the objects that I sense interest you most – the chambers, cairns and piles, are but a tiny fraction of a vast constellation of stone objects on the landscape, the vast majority of which are historic ruins of the colonial and Yankee eras.

Why these have interested professional academic archaeologists so little, has always been fascinating to me. I suspect it’s a legacy of history of American archaeology in the Old vs. the New Worlds.

In the Old World, early archaeology concerned itself with above-ground ruins. In the New World, and following the example of Thomas Jefferson, archaeology is principally concerned with excavation, usually “Of Small Things Forgotten,” the phrase used by James Deetz as one of the best book titles ever.

To my mind, the most important research question facing us today is how to sort out the certainty of a tiny bit of pre-historic stonework from the self-evident stonework of the historic era.

The answer for me lies in what I call my conceptual toolbox. In it are many tools that I have gathered over the years. But there are five tools that I return to time and time again.

when going about my work, depends on the employment of conceptual tools, which I dub: (a) Ways of knowing; (b) the parsimony principle, (c) the “good” hypothesis; and (d) the idiosyncratic factor.

My talk today outlines these four ideas prior to describing my four books, and leaving time for discussion from the audience.

WAYS OF KNOWING

If I have a problem with NEARA, it’s the same problem I have with hard-nosed scientists, religious leaders, culture-reinforcers… the never-ending and completely unnecessary collision between different ways of knowing, in this case four separate ways of knowing: tradition, intuition, science, and faith. Trouble intervenes only when one way of knowing intrudes on another to the point of trespass.

Robert Frost said it well when the said: Good fences make good neighbors. He didn’t invent that phrase, which originated somewhere in the Carolinas in the 19th century. But he sure understood it…at least well enough to write the most famous poem about New England stonework ever written. These boundaries between tradition, intuition, science, and faith must be acknowledged and respected if we are to make progress.

- Science = is another word for secular logic: For the question “How do you know?” it answers: “Because I can prove it.” Its key tools are the hypotheses, experimental trials, quantitative analysis, and comparative methods.

- Tradition = is another word for cultural habit: For the question “How do you know?” it answers: “Because this is what we’ve always known or done.” It’s key tools are ritual, the sharing of icons, and reliance of founding documents, a.k.a. sacred texts.

- Intuition = is another word for mystisicm or spirituality, knowledge that flows directly from the rational world of the senses to the irrational world of your emotional mind. For the question “How do you know?” it answers: “Because I can feel it.” Its key tools are solitude, experiencing the wild, meditation, and silent prayer.

- Faith = is another word for visceral or instinctive knowledge: For the question “How do you know?” it answers: “Because I know. I just know.” It has only one key tool, the trump card. Faith is the bottom of the metaphorical well, the place where we all go during times of deepest trial. There’s no arguing with faith.

America’s Stonehenge, in north Salem New Hampshire. provides a great example of the collision between different ways of knowing. I have visited there. I have read the signage, and its reports, and have seen its radiocarbon dating reports.

My intuition tells me that this is a special place, one with pre-historic archaeology. There’s nothing wrong with me being a scientist and also having intuition, for that’s where most good ideas come from… an irrational “flash of insight.” But I am yet to be convinced that the interpretations I read – for example the presence of the “sacrificial table” are correct.

Another example of such conflation is a bold assertion made in the very first sentence of Manitou: The Sacred landscape of New England’s Native Civilization, published in 1989 by James W. Mavaor, Jr. & Byron E. Dix. I bought this book nearly twenty years ago when I began to pay close attention to stone walls on the landscape. I really like the book, and have used it not and then to help me understand something I’ve noted on the landscape. What I do not like is its first sentence:

“The early seventeenth-century English settlers of America called the land New England because, among the reasons, it reminded them of home; they saw stone walls, standing stones and stone heaps like those of the English countryside.”

The documentary historic record for New England is at odds with this statement. It indicates that the first permanent attempt at English colonial settlement occurred in 1607 at the Popham colony at the mouth of the Kennebec River in what is now Maine. From their records, they saw nothing resembling the familiar English countryside. Nor did they call it New England. That name came from Captain John Smith in 1613, who used it as an advertisement to help convince others to settle. Further to the south, it is well known that Governor Bradford of the Pilgrim colony at Plymouth, MA imagined the land as a “hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men.”

A more serious problem is when two ways of knowing collide in the public arena and an acutal choice must be made.

What is an obvious stone pile to one person based on scientific observation looks equally obvious as a sacred stone pile to others using intuitive methods. A good example is the cairn at Thoreau’s house site in Concord MA, which has grown steadily and has morphed from upright architectural monument to sprawling pile, locally with more ordered piles. This sacred site, this destination for pilgrims, is a stone pile.

Non-scientists can easily become scientists by developing certain habits of mind. You don’t need a degree or credential to do science, though you do need one to do academic science. Because academia is an institution – like religion, business, the military, and government — its employees are more constrained than those of an interest organization such as NEARA. Institutions are constrained by history, rules of governance, means of earning credentials, and so forth. They are also constrained by anonymous peer review in which reviewers judge whether an conclusion is adequately drawn.

PARSIMONY PRINCIPLE

The second of these scientific thinking tools is the parsimony principle, also known as the law of parsimony, also known as as Ockham’s Razor. The basic idea is that, given two plausible competing explanations for the same observation, the simplest or most familiar is the most likely to be correct.

By using the phrase, “most likely,” I am affirming that the principle applies not to truth or falsehood, but only to probability of being correct. This parsimony principle is not proof of any kind. Rather, it’s a “rule of thumb” used to help in the framing of hypotheses, not a test of whether one is true or not.

By using the phrase simplest, I mean the one requiring the fewest and/or the least convoluted assumptions. Bt familiar, I mean the one that is most consistent with time-tested, local explanations.

For example, let’s assume an unusual stone pile amidst a population of ordinary stone piles. The parsimony principle requires that, in lieu of evidence to the contrary, the odd stone pile is just that, a pile of stones. Similarly, if the piles are located on an abandoned historic farmstead with a constellation of other stone structures, then the parsimony principle requires that they were built as part of farmstead activities. The burden of proof rests with the one promoting the non-parsimonious one.

My favorite expose of non-parsimonious thinking is Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories. All his stories are completely logical, for example why the elephant got its trunk or the leopard its spots. All are wrong. Just because something sounds logical doesn’t make it right.

HYPOTHESIS

Using the parsimony principle requires that a hypotheses be well defined. This is the third thinking tool I present today. And a good hypothesis is not necessarily that easy to create, as my students continue to find out to their chagrin, even those with good SAT scores, high class rank and passing grades in calculus, physics, chemistry, and the life sciences.

A hypothesis is a good question framed as a statement that yields a binary (yes/no) answer (for each attempt at falsification). This sentence requires some unpacking.

A good question is

- Novel: hasn’t been asked and tested before.

- Relevant: worth knowing. Relevance is culturally determined.

- Ethical: does no harm, or harm within culturally accepted norms.

- Testable: with observations or measurements.

Hypotheses become stronger each time they survive a test, often tests from different angles using different data sets.

Because science cannot prove something to be true, the best approach is to create a null hypothesis (the one you believe to be un-true), something that can be nullified by evidence. Basically, you set it up to knock it down. Then you set up another, which you also try to knock down. After a few trials, the one left standing is the one you suspected all along as being true. You try to knock it down repeatedly. If you can’t it’s accepted as being true.

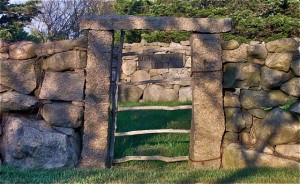

Let’s look at the lace wall above. Below are the explanations I’ve heard from experts (so-called).

- #1 – They’re built with holes to allow the spirits of Native Americans to pass freely over the land now bounded by stone “fences.”

- #2 – They’re precariously built because sheep are intimidated by the appearance, which makes it a good fence.

- #3 – The openings allow wind to pass through, preventing them from being blown down in gales.

After thinking about his problem for some time, I’ve added four more, none of which are probably original with me.

- #4 – The design is a pattern of folk art adopted by local farmers, copied from one to another fashion.

- #5 – The goal was to reach the legal height of a fence – generally shoulder high – but there wasn’t enough wood to raise walls that would otherwise be thigh-high, and not enough stones to go around. Hence, the “stretching” of material supply, like making the last bit of the toothpaste tube last.

- #6 – Though they look precarious, many actually are not. The frictional bond of a point-on-a-plane is often stronger than the bond of a plane-on-a-plane. For example, think of your stability on an icy driveway with skis vs. metal crampons or cleats). The former is a plane on plane. The latter is a point on plane.

- #7 – Perhaps the open-ness says more about a lack of small particles to chink the holes with, or with the difficulty of having small chinking stones stay in place in a single wall, being poked or blown out of place.

There you have it, seven explanations for the same phenomena. Some of these can be converted into excellent hypotheses. Some cannot. Probably the easiest to test is the one about wind. We could literally try to knock them down using the wind, seeing if a solid wall stands up worse than the ventilated one. An artistic tradition could be the true answer, one that just happens to coincide with the aerodynamic explanation, and which is difficult to test.

Another easy one to test is the hypothesis about frictional stability. Here one could get quantitative, summing the total friction.

Most hypotheses emerge from “IF-THEN” statements. They result from predictions of hypotheses that have already stood up to many tests. This “if-then” relationship explains why a hypothesis can – and should — be considered the footstep of science. On a physical journey, every step moves you forward and depends on the previous step. Likewise, every time you learn something, it generates a prediction that allows you to learn something more.

IDIOSYNCRATIC FACTOR

This brings me to the fourth and final thinking tool I want to share with you, the one that creates a thorn in the side of other hypotheses, and violates the parsimony principle. I refer to what I call the idiosyncratic factor.

People doodle. The do so for no apparent reason. They make marks on paper, ivory, wood, and stone because they are impulsive. Most people begin doodling unconsciously, recognize they are doing it, and then carry on fully aware.

Native Americans and New Englander farmers probably doodled quite a bit with their stones. Lurking in the background of our attempts to explain the odd stone structures of New England is a null hypothesis that’s very easy to set up, but almost impossible to nullify – that a feature exists for no good reason at all.

This concludes the main part of my talk. Now I’d like to add a finisher.

FINISHER

Earlier today, I heard comments about two things, which I’d like to share with you. Perched boulders and horned serpents coming up from the water.

The perched boulders on the cover of Manitou stones are glacial erratics. They may have been used for their spiritual siginifance, but their origin is geological.

My second example is that of horned serpents rising up from the lake. I do not discount the importance of native tradition on this score, for that was clearly shown this morning. What I suggest —as a hypothesis, and not even a novel one — is that the inspiration for the native motif is physical, a neutrally buoyant driftwood log intermittently raised by an internal seiche wave within elongated lake.

Alternatively, let’s think about stone chambers. When I was a boy in Illinois, I remember arranging deadfall logs and bark into shapes that resembled some of the more poorly built stone chambers I’ve seen in New England. We did so to make a clubhouse. When I was a teenager in Minnesota, I did something similar to make a private place for romance. I am not suggesting that New England’ beehive huts were built for that purpose. What I am suggesting is that that explanation must be set up and ruled out as a null hypothesis before moving forward, whether formally or informally.