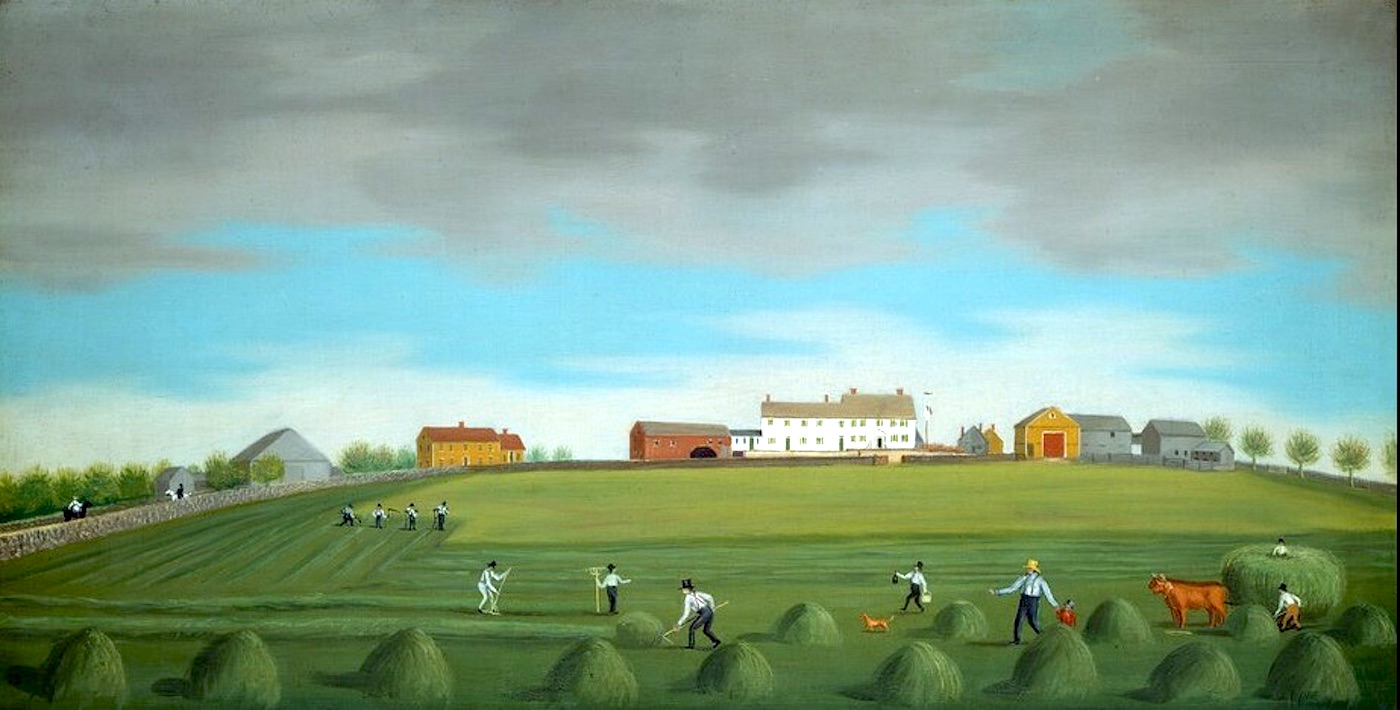

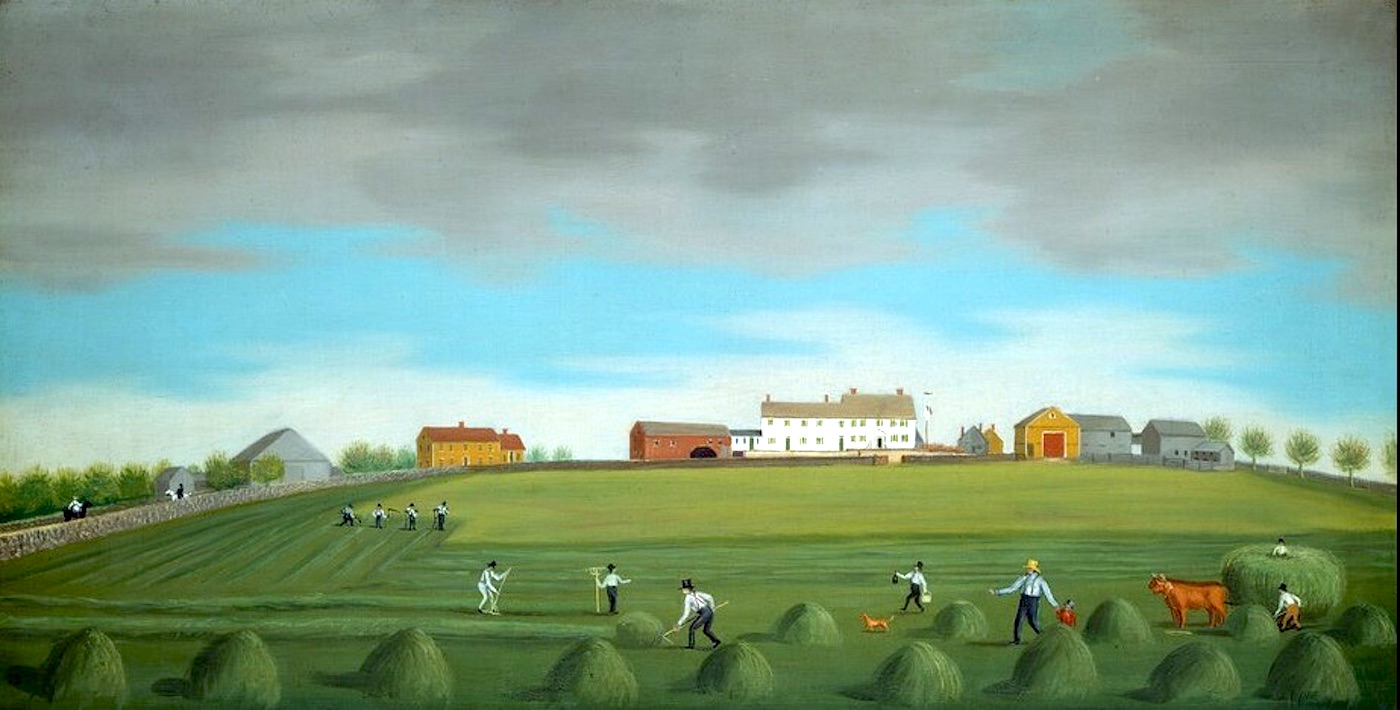

“Ralph Wheelock’s Farm.” Francis Alexander (American, 1800-1880), c. 1822, oil on canvas, 122 x 64 cm. National Gallery of Art. Gift of Edgar William and Berenice Chrysler Garbisch, 1965.

A picture is worth a thousand words. Sometimes, this time-worn cliche is astonishingly accurate. as with my re-discovery of this painting this spring. Having been invited to Yale University’s Agrarian Studies Program to discuss my latest book (The Boatman, Harvard Press, 2017), and wanting to know more about the program, I googled it, and this is the image that popped up. This large oil painting captures the totality –point by point– of my summary description of New England’s lodgment till landscape published in my book Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls (Walker/Bloomsbury, 2002):

“Lodgment till is almost singlehandedly responsible for rural New England’s bucolic image–gracefully curved hillside pastures framed by stone walls.”

I was so stunned by the match between this painting and my text that I immediately began to write this post, which asked if some reader “out there” could provenance the painting. Paul Barnett responded, and I thank him for that. When acquired by its first known owner, Colonel Garbisch, the painting was originally named “Dennison Hall, Surbridge, MA.” Subsequent research revealed that there was no such place, but there was a Dennison Hill in nearby Southbridge, MA that looked like the painting, complete with a white house built in 1765 by captain Ralph Wheelock. Hence the painting was twice retitled, first to “Dennison Hill, Southbridge” and then to “Ralph Wheelock’s Farm,” based on information published in “American Native Painting” by the National Gallery of Art based on research by Arthur Kingston Wheelock, dated June 2000.

So, when viewing the photo at the National Gallery of Art (linked here), I ask that you contemplate the match between the picture and the ~1000-word text.

Travels in New England and New York (1815) by the Reverend Timothy Dwight is arguably the most widely read and appreciated overview of New England scenery during the years of the new republic. Here’s what Dwight –the widely traveled president of Yale College– had this to say about the soils beneath the fertile uplands of his southern New England landscape.

The hills of this country and of New England at large, are perfectly suited to the production of grass. They are moist to their summits. Water is everywhere found on them at a less depth than in the valleys or on the plains. I attribute the peculiar moisture of these grounds to the stratum lying immediately under the soil, which throughout a great part of this country is what is here called the hardpan.

His summary links the words: hill, grass, moist, stratum, soil, and finally, hardpan. Reordering these words as narrative, we get: hill, stratum, hardpan, summits, soil, moist, and grass. Here’s my geological explanation of Rev. Timothy Dwight’s summary.

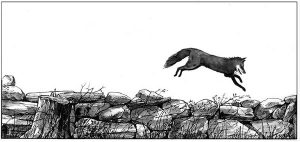

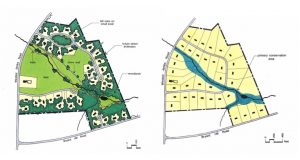

During the last glaciation, the hills of southern New England were high enough to be fairly resistant to glacial erosion. This led to the preservation of an older stratum of hardpan (technically, a lodgment till) beneath the broad summits. Though stones are present, this material easily disaggregates to create a highly fertile, loamy mineral soil, yet remains moist because it is impervious to rain and snowmelt percolating downward. The combination of high fertility and high moisture is perfect for the production of grass, New England’s historically most important crop, whether grazed a pasture and cut for hay. For this reason, the hilltops were sought after, their stones easily moved downhill and stacked into walls.

Now here’s the longer quote from Stone by Stone explaining why this material was so sought-after.

Lodgment till was a gift to the pioneers, with or without the stones. It provided a physical barrier that blocked the seepage into the earth of rainfall and snowmelt. This kept the soils moist, gave rise to perennial springs, and trapped the water in small ponds needed to water livestock. Agricultural soils developed on lodgment till were highly fertile because they were composed of microscopic pieces of glacially pulverized minerals that provided an enormous surface area for biological reactions in the soil, especially those that feed nutrients to plant roots. Lodgment till also produced a terrain of smoothly rolling hills that were usually steep enough to let the water drain away, yet gentle enough to prevent surface gullying. Rock hard beneath the surface, lodgment till was strong enough to support the largest barns. Finally, the gently rolling till-covered landscapes allowed easy movement of humans and their creatures because there was little need to build bridges or avoid rock crags.

In short, my summary reads: “Lodgment till is almost singlehandedly responsible for rural New England’s bucolic image–gracefully curved hillside pastures framed by stone walls.” This is the material that lies beneath the canvas of Francis Alexander’s 1822 painting Ralph Wheelock’s Farm, and beneath the New England psyche as well.

Perhaps that is why this painting was chosen by Yale’s Agrarian Studies shows for its home page.